Underwater Basket Weaving

The Setup

"The bride is a graduate of Prairie Dog Tech, where she received her degree in underwater basket weaving. Her other pursuits of study were familiar bird calls, Egyptian folk dancing and men."

–1952 April Fools' Day article announcing "Chlorophyll I.S. Green Marries Ima Violet Cloud in April 1 Rites" (The Rock Island Argus, 4/1/1952)

I’d like to apologize up front to all the liberal arts majors reading this, surely flashing back to the most annoying conversations they’ve ever had. Any college student majoring in any subject besides the most career-minded and “practical” has heard this phrase. Nothing delights an uncle more than to tease his nephew over Thanksgiving dinner: A philosophy degree? Was underwater basket weaving full up?

If the phrase needs any explanation at all, it’s because it has journeyed so far into the wormhole of cliché that it has emerged in another galaxy as meta commentary on itself. Once a patronizing way to describe easy, useless, or navel-gazing courseloads, “underwater basket weaving” has been the subject of countless ironic projects, including “real” versions of the course. Some anthropologists have even tried to reclaim the phrase, arguing that it denigrates the crafts of real-world cultures.

So the meaning of the phrase is well understood. The history, however, is less so. In my research, I’ve found plenty of incomplete or spurious origin stories, including false claims that have circulated in the information wasteland of the internet. No writer to my knowledge has constructed a single definitive story. This, I hope, will fill that gap.

We actually start outside of college entirely. The first people annoyed by basket weaving were not students or faculty but soldiers returning from World War II. Basket weaving was one of many activities used in the relatively new field of occupational therapy. Weaving, knitting, and other crafts were (and still are) believed to help people with mental disorders, which included traumatized soldiers.

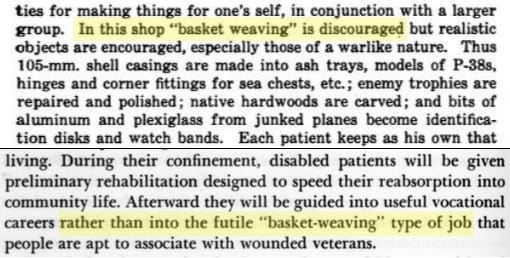

A 1945 Navy report on treating “combat fatigue” already uses the phrase in quotes. “Basket weaving” was being used as a kind of activity rather than the activity itself, and soldiers vocally resented such tasks. These crafts were seen as pointless make-work, suitable for the severely disabled but not soldiers who considered themselves higher functioning. The Navy recommended men work on objects “of a warlike nature” instead. (Hell yeah brother.) A 1946 report from the National Conference of Social Work also threw scare-quotes around the phrase, calling such work “futile.”

You might assume that this reaction was normal for the time, that if anything therapists should have expected it. Of course a fascist-fighting veteran in the 1940s would sneer at childish crafts. But crafts classes were used for returning World War I soldiers as well, and the classes were reportedly popular. One story states that basket weaving was the best attended class, and space had to be expanded to meet demand.

!["So many of them are now wanting to put in their time at [basket weaving] that the commission is being forced to expand its quarters"](https://www.imightaswellexplainthejoke.com/content/images/2026/01/Keeping-the-mind-busy-by-basket-weaving---The-Sunday-Oregonian--6-19-1921.jpg)

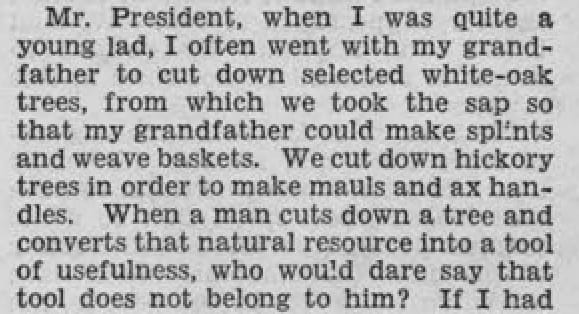

You might also assume basket weaving was stigmatized as women’s work. Examples of misogynist stigma do exist, and as the century progressed the craft became more associated with women and children. (It also had an association with "primitive" cultures, particularly Native Americans, a larger topic than can be addressed here.) But plenty of men were basket weavers too. In the congressional records of 1949, Senator John L. McClellan reminisced about making baskets with his grandfather. McClellan was no progressive: he was a segregationist and is here railing against the evils of socialism. Yet he depicts a stoutly masculine scene, of men mastering nature and, yes, weaving baskets.

The difference, I think, is that basket weaving was a regular, useful skill to have in the first half of the twentieth century. It was an everyday craft and profession. Basket weaving courses were on regular offer in towns across the country, and locals received them enthusiastically. Proving that these courses were received both locally and enthusiastically will require a close examination of the historical record, synthesizing various records across the cou–oh wait, no, here’s a headline that just says exactly that.

As basket weaving (alongside the entire world economy) became industrialized and globalized, and handwoven baskets became more of a craft project for scout troops and ladies clubs, World War II offered us a strange social experiment. What happens if you put scores of troubled young men into rooms full of unassembled straw? What happens if, for no reason besides historical accident, you force thousands of men to form an opinion about the usefulness of basket weaving all at the same time? What should have been an unremarkable obsolescence, yet another of a million jobs absorbed into the global factory, became the “Twitter main character” of its day, a topic America’s veterans were forced to confront.

Eventually, the war ended, the GI Bill sent millions to college, and yuks could resume. We finally come to the actual jokes of this joke blog. Now that “basket weaving” had penetrated American culture as a metaphor for a useless craft, more elaborate forms surfaced. The earliest jokes I can find are two sarcastic uses of “honor basket weaving” in 1946 yearbooks, one a Massachusetts high school and another an Ontario university. A 1947 medical journal makes a crack about acquiring a PhD in “basket-weaving in the Nile Valley.” I want to emphasize the age range here, from teenagers to career professionals.

And here, finally, is the joke itself, the earliest instance I could find, attributed to a “Jim” in the 1947 yearbook for Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. At some point circa 1947, the already laughable concept of basket weaving was prefixed with the absurd “underwater”–perhaps even the invention of this Floridian Jim. Rollins College is, for what it’s worth, located directly on the shore of a small lake.

I also wonder whether a young man might have been referencing (consciously or not) Esther Williams, an actress famous for fanciful underwater routines, including an underwater ballet in 1946’s Ziegfeld Follies. But this I admit is speculation.

The joke quickly took off. The “underwater” form would become the standard, but early on there was some variation. The joke ran rampant in yearbooks–a 1950 Cleveland yearbook includes one student who joked about going off to study “Ancient Babylonian Basket Weaving.” But it wasn’t just students: the culture at large glommed onto a new phrase they could use to disparage college students, whether underwater, Babylonian, or the unflavored original. This Thimble Theater comic from 1948 includes basket weaving alongside music appreciation, another classically worthless course.

There is a universe where the story ends here. Basket weaving could have been a historical blip, a short-lived joke about a once useful craft becoming obsolete, no more remarkable than the extinction of cursive or DOS prompts or dedicated VHS rewinding devices shaped like race cars. But America was not just experiencing a surge in college students: multiple overlapping social crises related to college life peaked at this time. Each of these crises is a volume in itself, the subjects of books and articles and video essays plagiarizing those books and articles, but I’ll summarize them here.

The first was the GI Bill itself. For those unfamiliar, the GI Bill was an enormous benefits package for World War II veterans, a generous social program in some ways and scandalous in others. Notoriously, many black Americans were denied benefits. For our purposes, diploma mills are the scandal in question. Diploma mills were not new, but these scam schools became an urgent problem, offering phony degrees and preying on naive, first-time students (and their federally provided purses). This issue reached President Truman and led to amended legislation that denied funding to “avocational” courses.

The second crisis was corruption in college sports, the topic being made fun of in Thimble Theater above. College sports were racked with scandal. Paid-for ringers undermined the legitimacy of athletic programs and challenged the integrity of the colleges themselves. College athletes today still have a reputation for taking easy courseloads, but the image of athletes coasting by in trivial “snap courses” stems from this period. This was a massive story in America, widely covered in national media and debated in Congress. Both private colleges and state governments considered banning college sports outright.

The third crisis was the Cold War. Colleges were a locus of both socialist organizing and Red Scare fearmongering. Professors then, like now, were accused of indoctrinating America’s youth. Those youths were also criticized as lazy freeloaders or worse, paradoxically both vulnerable children and agents provocateurs. Free-market pearl-clutchers worried that the government was paying students to loaf on quads reading Marx rather than become productive members of a capitalist economy.

Across all these crises, commenters needed a metaphor for an easy, fraudulent, or even treasonous course. In all these situations, such courses threatened the American way of life. But naming specific courses might prompt granular arguments. Truman, for example, spoke out against the GI Bill paying for dance and aviation courses. Sure, dance classes are of dubious capitalist value, but what did Truman have against pilots? Someone must have piped up–in future legislation, funding for dance classes was eliminated while flight class funding was merely reduced by 25%.

Nobody, however, can pipe up for “underwater basket weaving” because it doesn’t exist. Critics spoke about such classes as if they were real and could equivocate if challenged. And so underwater basket weaving congealed into the go-to idiom we know today, deployed by everybody from your annoying uncle to sitting senators.

The Punchline

Some jokes endure for the self-evident reason that they're really that funny. I’ll always laugh when Bugs Bunny fucks up playing “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms” on Yosemite Sam’s piano. It’s a good gag!

Underwater basket weaving sits a bit lower on the joke tier list. It’s unclear to me whether it was ever considered amusing. Whatever thrill was had reading the phrase in 1947, it is hard to imagine the joke has elicited more than a polite chuckle since the 50s. It is the kind of comment that in the group chat you hit with a thumbs-up reaction instead of a laughing face.

But it is useful, and that’ll keep a joke alive for a long time. What should have been a zeitgeist-y metaphor with a short shelf life overlapped with a new and permanent need in American culture to degrade the work of students. A joke of the moment became a tool for the future–because it turns out that we have a regular need to degrade our students, to fabricate panics and promote the fantasy that public school funding is not merely wasted but actively corrupting our children.

In 2025, only last year as of this writing, republican legislators promoted a conspiracy that public schools were installing litter boxes for students who identify as animals. Texas state representative Stan Gerdes introduced legislation banning this imaginary practice. In a hearing, he was asked to prove that this had ever happened. All he could mumble was “We’ve gotten some reports.”

And if I was writing in 1962, I could point to the words of congressman Edgar W. Hiestand, who opposed an expansion of federal funding for higher education. He argued that educators, unless strictly controlled, go buckwild with the kinds of courses they dare to teach–including basket weaving. Just as Stan Gerdes claimed to have “gotten some reports,” Hiestand claimed to be “reliably informed” such classes were real.

It is not, of course, that students never practiced such crafts. Hiestand mentions folk dancing alongside basket weaving, and you can find folk dancing courses in real colleges over the years–including, incidentally, at Rollins College in 1947. But it misses the point to debate the reality of these courses. They are shorthand for a crisis that is decidedly not real: that America’s students are coddled and overeducated, living lives of pretentious decadence paid for by Americans with “real” jobs.

Right now, in fact, republicans are actively downgrading job qualifications, seeing any college degree at all as an extravagance. In 2023 representative Nancy Mace (pause for crowd to finish booing) wanted to remove degree requirements for federal cybersecurity positions, conflating the very idea of a college education with, wouldn’t you know, underwater basket weaving. It still shambles on.

Some 75-plus years after its invention, the phrase has undeniably lost its edge. It has long been a dead metaphor, empty of imagery and emotional impact. Whatever bite it once had, it’s got none now. One day, I’m sure, another phrase will take its place. But no phrase so far has sunk its roots so wide and so deep. Until then, liberal arts majors across generations get to share their annoyance at this one.

Postscript

In researching this post, I encountered a variety of theories for the origin of underwater basket weaving. I'm skipping the normal background reading section because this post is driven by original research. I will acknowledge that there is still no definitive first use of the joke, no one person we can conclusively say coined the phrase, and so few theories can be eliminated outright. We live in a McWorld, after all–hey, it could happen. I’d like to address two prominent theories, though, and why I think they are probably wrong.

In the early 50s, several newspapers reported that “underwater basket weaving” was teenage slang, the latest confusing jargon from America’s youth. One such newspaper was The South High Tooter in Omaha, Nebraska. (Unrelated, the Tooter featured a regular column called “Tooter Teen” where every week a teen in the Tooter was awarded the title of, you guessed it, Tooter Teen.)

While students were obviously using the phrase, it was quite mainstream and not the sole purview of hep cats. As I mentioned above, people of all ages were making fun of “basket weaving” courses. I believe its association with occupational therapy is the more likely origin. Cool kids throughout history can claim many phrases, but I do not think underwater basket weaving is one.

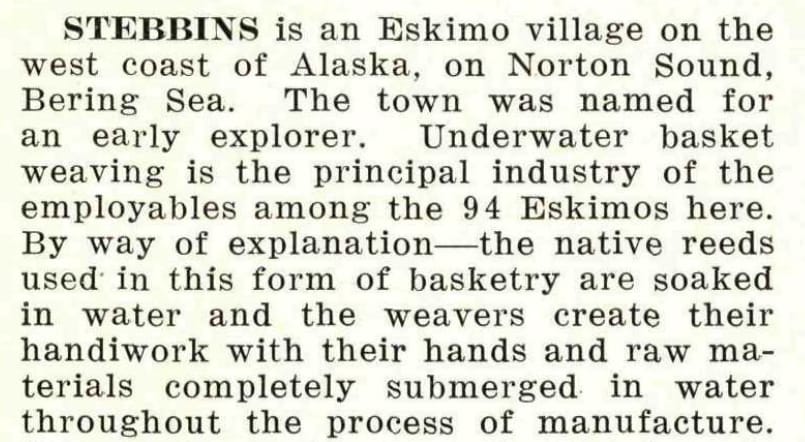

Another common idea I’ve seen, often posited by online commenters, is that underwater basket weaving might have been a real-world tradition that directly inspired the joke. The phrase appears unironically in a 1956 volume of The American Philatelist. (A philatelist is what stamp collectors call themselves to sound even sexier.) The magazine describes basket weaving done by indigenous Alaskans (probably Yupik, though the magazine calls them Eskimo) while the reeds are literally held underwater.

It does seem to be true that “underwater basket weaving” exists in real cultures, but I believe the relationship between these real practices and the fake college course is pure coincidence. That issue of The American Philatelist, for example, post-dates many examples of the joke. It also happens to be one of the earliest hits in the Google Books database–the kind of free online resource from which an amateur historian might draw hasty conclusions. I have found no use of “underwater basket weaving” that suggests it was a topic of sincere anthropological interest before becoming a gag.