Frivolous Lawsuits

The Setup

Let’s get it out of the way because you’re probably thinking about it. This is not going to be about Liebeck v. McDonald's Restaurants, the infamous 1994 lawsuit where an elderly woman sued McDonald’s after burning herself with hot coffee. You know that story, I know that story. Anybody who can name “a frivolous lawsuit” will probably name that one. I want to cast this net a little wider.

And I do mean pretty wide–wide in that grumpy old “what the world is coming to these days” kind of way. We’re going to be talking about, more or less, modern America itself. Big topic! If it helps, you’ll get to see a Ziggy comic before the end.

Imagine yourself back in the 1970s. Richard Nixon has resigned in disgrace, setting the stage for the go-go Carter years. You just walked out of William Friedkin’s Sorcerer, thrilled by sweaty men driving rickety trucks. And if anybody was spilling coffee on themselves, they suffered in dignified silence. But the world was changing quickly, and in particular the legal system seemed to play a much bigger role in civil society.

You are in the middle of what would be known as the “litigation crisis.” This was, let’s be clear, a real concern among Americans, both laypeople and legal professionals. We’ll get to the frivolity of the lawsuits soon, but there’s no denying that there were more lawsuits and more lawyers in the world. It was only the previous decade, for example, that the Supreme Court determined that Americans were entitled to a lawyer in criminal cases. Gideon v. Wainwright was ruled in 1963. That ruling, while far from the main driver of lawsuits, was a bellwether.

More cases, and more legal rights, meant more lawyers, and the legal profession ballooned by tens of thousands. Law students offered their services in pro bono legal clinics, expanding who could afford a lawyer in the United States. In particular, the country saw an influx of women and nonwhite lawyers unlike any time before. Uh oh! I think you know where this is going.

Maybe as bad as an increase in women lawyers was an increase in lawsuits based on feelings and emotions rather than concrete damages. The term “mental anguish” became shorthand for these sorts of lawsuits–mental distress being an obviously ridiculous reason to sue someone. To claim mental anguish was to admit to being a phony.

There probably wasn’t a real increase in civil litigation–not the kind we’re talking about. Certain kinds of cases boomed, and the US population was on a steady climb, but the country probably wasn't seeing a surge in the damage-seeking, big payday, interpersonal litigation that defines the frivolous lawsuit. Nonetheless, big-name commenters claimed the country was cast in the shadow of a legal and, more so, moral failure. If you've ever heard the phrase “tort reform,” this is what it's about. No less than Chief Justice Warren Burger decried an overly litigious public, arguing that Americans had forsaken traditional social remedies in favor of the courtroom.

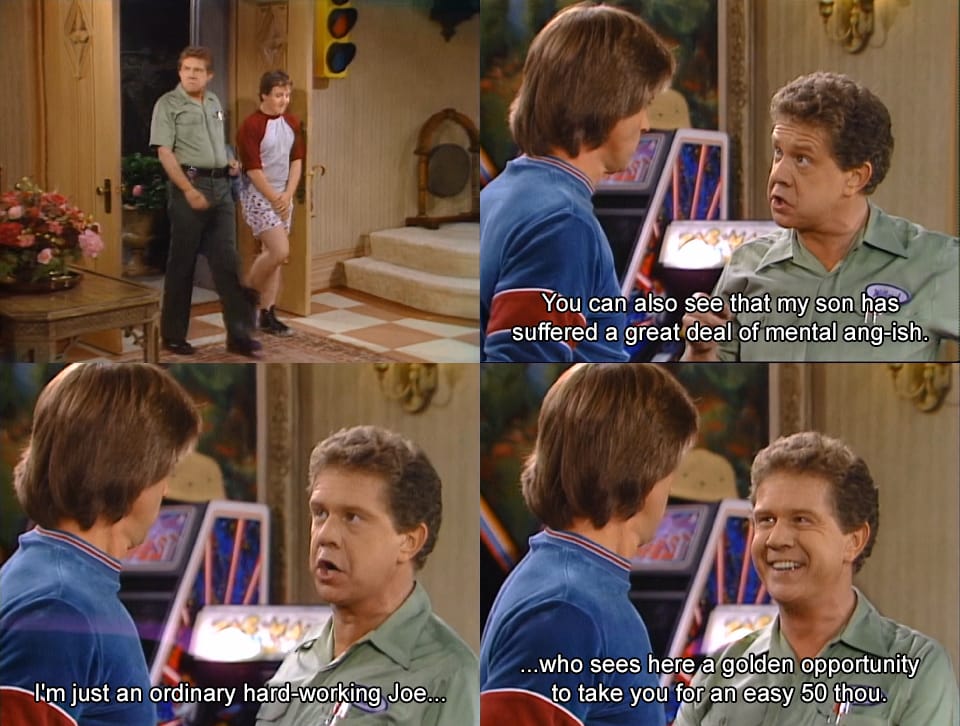

An example might help. The 80s sitcom Silver Spoons offers a snapshot of these lawsuits. The show follows the Strattons, a wealthy family who–I mean, who cares. It’s not very good. It’s the show Jason Bateman was on as a child. Just know the family in Silver Spoons is rich.

The 1983 episode “Twelve Angry Kids” provides a perfect summary of how American culture viewed lawsuits at the time. In the episode, Ricky Stratton (the wiener kid protagonist, not played by Jason Bateman) gets in a fight with the school bully Ox, somehow managing to pants Ox in the process. Ox’s father, a money-grubbing poor (blatantly characterized as working class), enlists a celebrity lawyer to sue the Strattons for all they’re worth. He deploys the phrase “mental anguish” but is too poor to know how to pronounce it.

If you can only watch one piece of media that encapsulates the whole frivolous lawsuit thing, watch this episode. It covers all your bases: a trivial inciting incident blown up into a get-rich-quick lawsuit, a duplicitous plaintiff, a big-time lawyer, and a sympathetic judge. During the trial, Ox the bully cries “whiplash,” an injury that is real but had a reputation for being faked.

Above all that, the episode makes clear an important point: this is uniquely modern bullshit that real Americans shouldn’t have to deal with. The episode doesn’t end with the judge dismissing the plaintiff’s $67,000,000 claim (increased from $50,000) because it’s ridiculous. The plaintiff is revealed to be a fraud, but that’s not why he loses. He loses because Ricky Stratton, our hero, testifies that he did attack Ox, but he attacked Ox because Ox insulted Ricky’s father. Ricky was defending his family’s honor.

This was just a regular, everyday dispute among regular, everyday Americans. Nobody was seriously hurt. And if somebody was hurt, it was justified, because you can’t insult a kid’s father and not expect him to fight back. Bringing this to a courtroom is not just oversensitive, it’s not just greedy, it’s un-American. At least, how America used to be.

The Punchline

The cultural anxieties here are plain to see. Oppressed groups were gaining new rights and asserting old ones, and the legal system was the arena where they secured those rights. The law used to be the pretense for power’s legitimacy, where injustices could be polished to a civilized sheen. Now the law began to make slow, toddling steps toward what you could unironically call a justice system. That just wouldn’t do.

The unfortunate outcome is that the people who needed legal protection lost this battle. The specific concerns of that moment, whether some amount of tort reform was necessary, morphed into a widespread belief that lawsuits were for pussies. The frivolous lawsuit became such a self-evident reality that it transformed into a kind of human interest story. We all know there are opportunistic freeloaders out there, that’s just how the world works. We not only know it happens, we expect to hear about it. Now please enjoy these humorous books for your coffee table or bathroom.

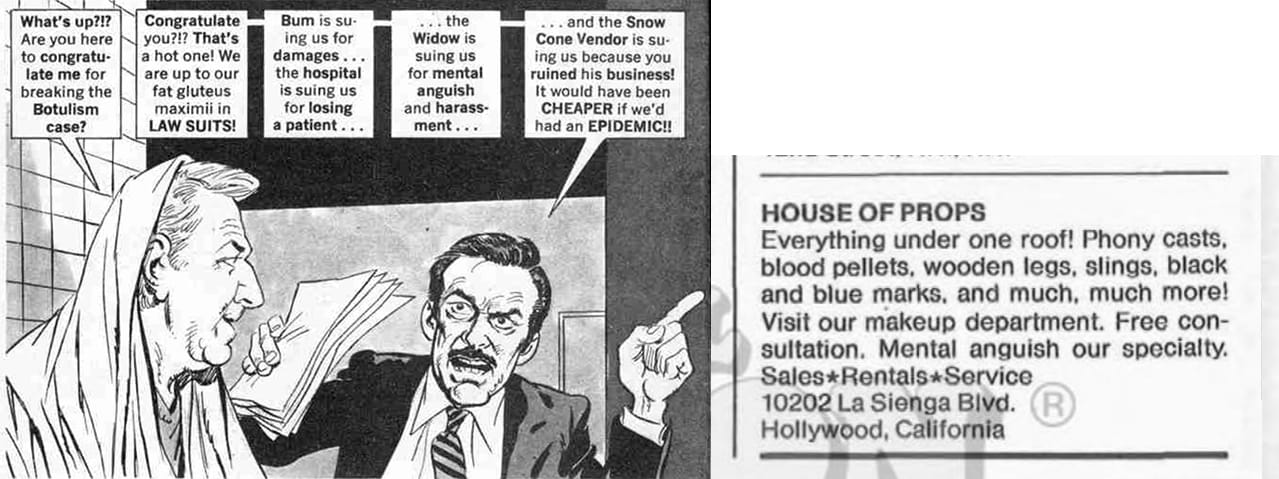

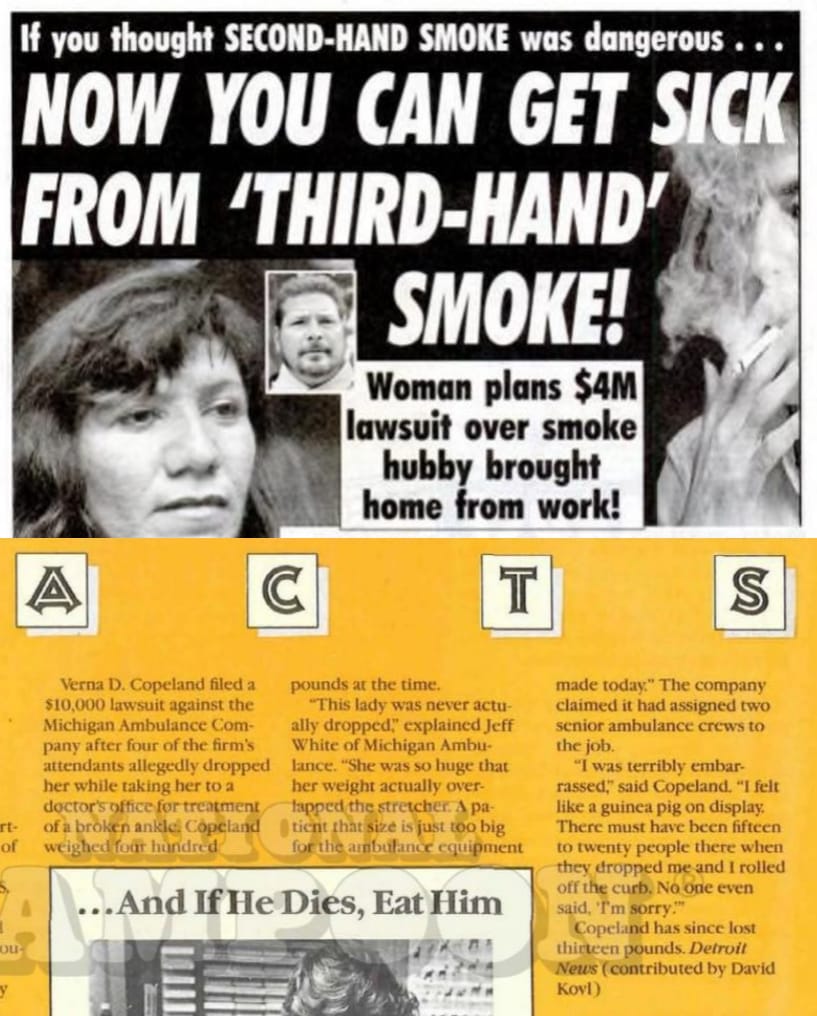

Eventually, the frivolous lawsuit started to emerge as its own comedy format. The stories became ironic tales, not judgmental of the plaintiff for being greedy (that was assumed) but for more pointed moral shortcomings. These stories were lessons, Aesop’s Fables for America’s dullards. Many were plainly exaggerated or fabricated, and many were intended to be read as jokes. They still mattered because they felt true.

National Lampoon and Weekly World News printed countless variations on this theme, from a fat woman (how dare she!) who caused her own injuries (by being fat) to a story that takes the already laughable concept of second-hand smoke to its absurd conclusion. The (now moralized) frivolous lawsuit became a feature as essential as the weather report or your horoscope.

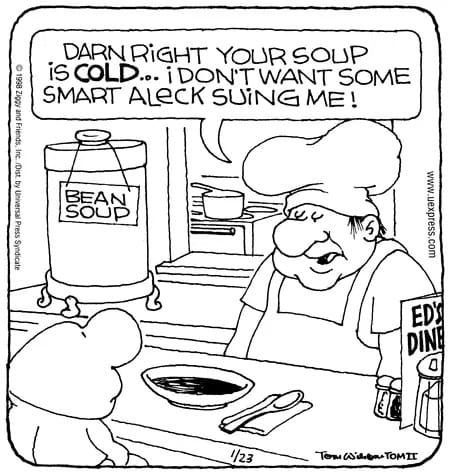

If you follow the chain long enough, you will reach Liebeck v. McDonald's Restaurants, a lawsuit now known equally well for being completely justified. I’ve personally witnessed many conversations where someone (usually quite thrilled to be doing so) explains that in fact the coffee was too hot and McDonald’s was in fact dangerously negligent. Little did you know, you naïve child, that this Ziggy comic was actually a corporate psyop, propaganda for the wealthy.

This isn’t an essay about the Liebeck case because I think it's less an illustration of the trend and more a victory lap by corporate forces. The bad guys had already won. When that old woman suffered an injury caused by corporate negligence, she was doomed to be a joke. Liebeck received a few million dollars in damages, but McDonald’s was the good guy. The largest corporations on earth received yet another story they could use to claim to be under siege by America's greediest parasites. That snake Ziggy really was caping for billionaires.

And that story had a powerful ingredient: nostalgia. The jokes about these lawsuits were often racist and sexist and classist–unambiguously and sometimes triumphantly so. The nostalgia, however, sits at the center, a false memory of a time when Americans were American. Back then (whenever "then" was), men resolved their differences in an honest, independent, bootstrap-pulling, self-relying sort of way. It didn’t matter how any given dispute was settled as long as men–and only certain men–did the settling.

And also Cathy.

Background reading

Moliterno, James E. The American Legal Profession in Crisis: Resistance and Responses to Change. 2013.