Coffee Breaks

The Setup

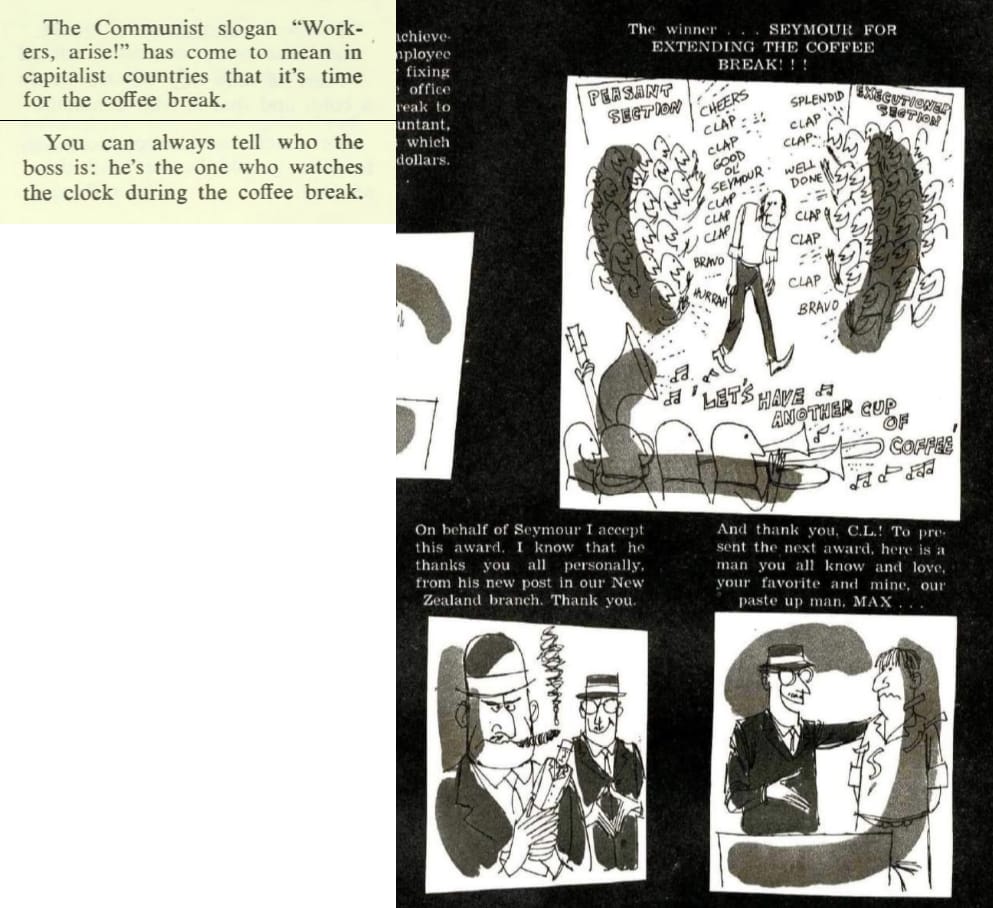

“In some government offices there are so many coffee breaks that the employees can't sleep at their work.”

–Evan Esar, 20,000 Quips & Quotes, 1968

This is, fortunately, not an essay about jokes like “Don’t talk to me until I’ve had my coffee.” There’s more interesting history I want to talk about, and besides, the coffee break is today so banal an event that the joke has become how painfully banal it is. People who make cutesy jokes about needing their coffee are (rightfully) scorned. One of my greatest fears is that at any point a coworker might think I sound something like this:

You are instead about to witness a rare collaboration between labor agitators and the advertising industry. Coffee breaks, despite seeming like the most natural thing in the world, are a pretty recent development. No single person invented the idea of humans enjoying coffee, but the origin of the quote-unquote coffee break is often traced to two ad campaigns.

The first campaign arrives in the 1920s. The agency N. W. Ayer & Son launched a series of ads promoting breaks for coffee (but not "coffee breaks") on behalf of the Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Committee. A copywriter named George Cecil worked on the campaign and has been credited with inventing the concept. In the great historical game of telephone, he has even been credited with coining the phrase itself, but none of the ads I've seen include the phrase verbatim. The second campaign in our story will come a few decades later.

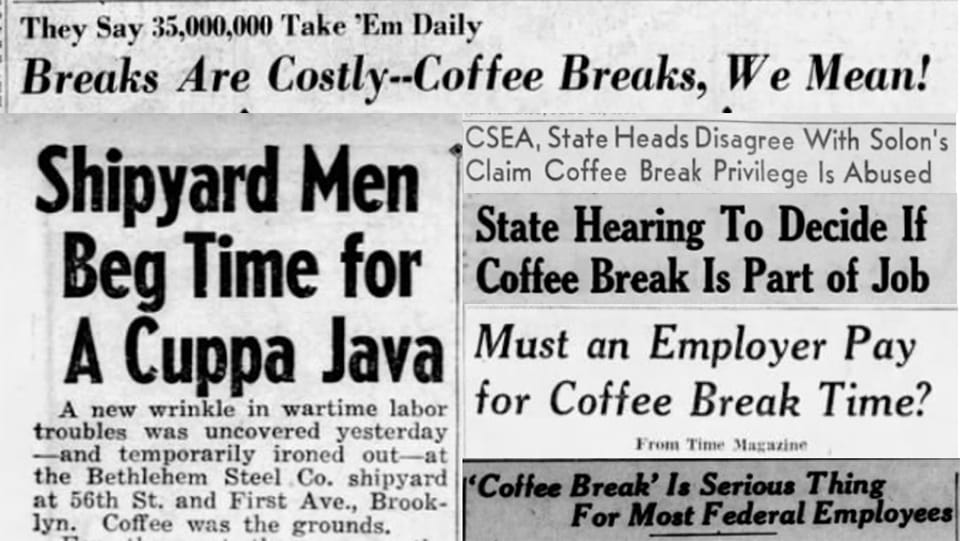

It won’t shock you to learn that taking a break from work to drink coffee was a very popular idea. Based on newspaper mentions, the specific "coffee break" phrasing gained momentum in the 1940s and was widespread by the end of the decade, and the coffee industry smelled profit too. Coffee started to make corporations a whole lot of money, with a 1954 Federal Trade Commission report claiming the drink had become “essential” to the vast majority of adults. The planets aligned for both corporate forces and rank-and-file workers to benefit from this craze.

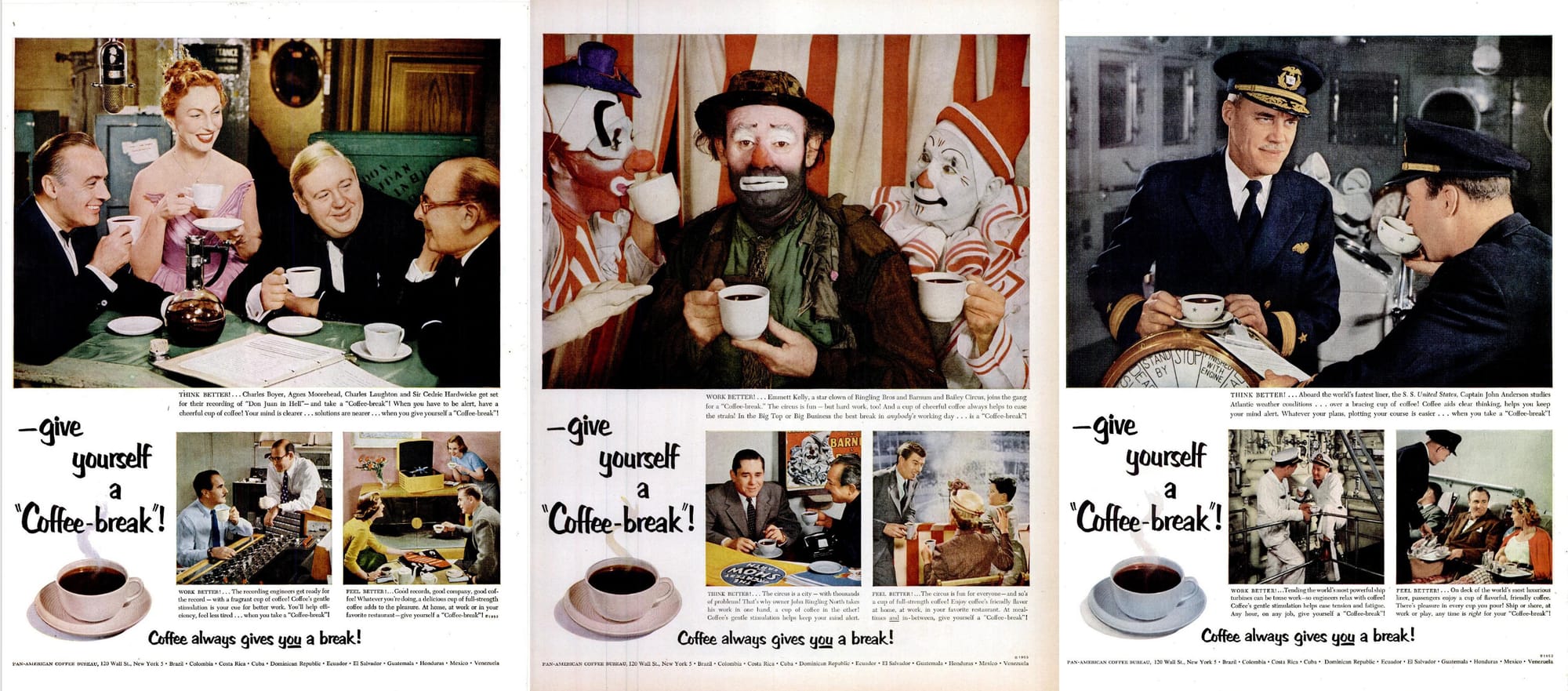

And a craze it was. The coffee industry became incredibly lucrative and corporations did not fuck around. The media was awash in ads and news coverage. Here we find our second ad campaign, arguably the single most influential moment in this saga. The Pan-American Coffee Bureau ran a coffee-break awareness campaign in dozens of issues of LIFE throughout the 50s. These ads have also been credited with coining the phrase, and they also did not, but they certainly promoted the shit out of it. Any worker somehow unfamiliar with the phrase could no longer escape it.

Importantly, the US government owned coffee roasters too, primarily for the military. The fed had been making a lot of coffee for the troops–World War II had just ended and the Korean War was popping off–and so the size of this industry was not theoretical. There was a huge preexisting customer base in addition to the dreams of an expanding market. Coffee companies saw both consumer potential and an opportunity to privatize a semi-nationalized industry.

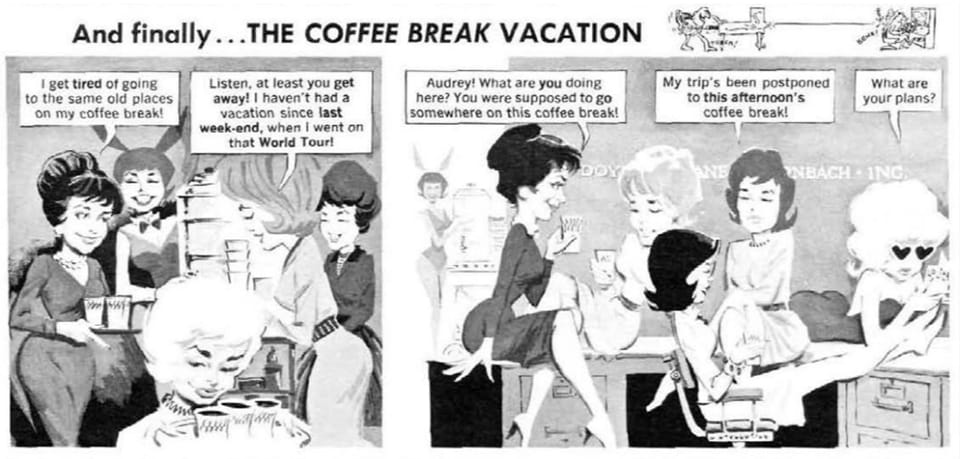

If today a coffee break is seen as a relaxing treat, at the time it was a “stampede,” a mad rush by workers thrilled to be enjoying their newly won recess. Far from loafers, coffee-break-havers were made fun of for their energy. Employees were excited and animated, less workers in need of a pick-me-up and more animals to be corralled.

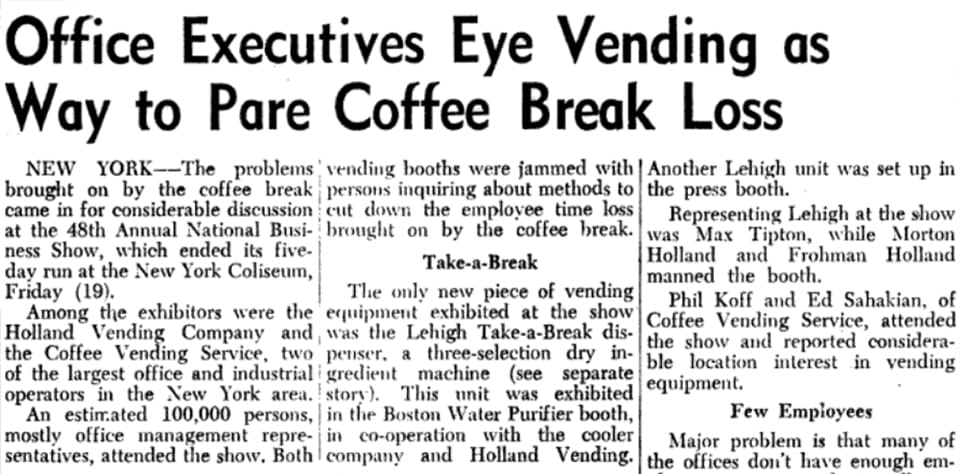

If coffee companies and workers were happy, the C-suite was not. They were, in short, terrified, praying the coffee break would be a short-lived fad. Corporate literature was rife with analyses about how much money companies were bleeding in lost time. Despite practically unanimous studies stating that coffee breaks led to happier and more productive workers, managers wrung their little hands over the perceived loss of work-hours and, I would safely guess, the loss of a little bit of their power in the workplace.

The coffee break was, in other words, a labor crisis. Workers wanted it, management didn’t want to give it to them, and comedians attempted to process this new phenomenon. (A break? At work?!) The coffee break was teased as a quirky new trend, but make no mistake that the public understood it as a labor issue.

I opened with a line from Evan Esar’s 20,000 Quips & Quotes because, first of all, that’s an impressive number of quips and quotes, and second of all because he offers two more quips that show us the clear political dimensions of the coffee break. He wasn’t making political hay out of nothing here, he was joking about something everybody understood to be a political topic. We can also look at a 1960 comic from Sick magazine where an employee is disappeared by a cigar-munching boss after securing a longer coffee break for the office.

Some comedians, less charitably, took the boss’s perspective, portraying time-thieving employees trying to squeeze the company out of every possible minute. A cup of coffee was a useful metaphor not just for idleness, but for a coddled, undeserved idleness. Often these employees were women, chattering and frivolous, children to be disciplined by the daddy-surrogate boss. It is these less charitable jokes that would become the mold for the coffee break in the future.

The Punchline

And, of course, there was a future. The coffee break became a normal part of American work life. The political agitation of the moment passed and workers won. Coffee breaks, and specifically coffee breaks, were negotiated in union contracts and discussed by the National Labor Relations Board and demanded in workplaces across the country. Eventually this was just how the world worked, even if progress did not come all at once or to everybody equally, as this comic in a 1962 issue of Negro Digest (later Black World) makes fun of:

Comedians continued to deploy the coffee break as a symbol of professional laziness (especially among government workers–the coffee break became another cushy perk enjoyed by state employees). Over time, though, these jokes felt more like observations of everyday phenomena. “Taking a coffee break” was one of the American worker’s natural states, a premise as broad as a man entering a bar or two people stranded on a desert island. This MAD comic from 1981 still uses scare-quotes around the term, but you can sense that this is well worn territory by the 80s, cheap pulp for the joke mills.

I think the coffee break is a typical American success story in two ways. It is, on its face, a story about ad men who light a fire under the American workforce, leading to a common-sense, win-win outcome. Coffee companies sell more coffee, workers are happier, and management comes to their senses to enjoy the fruits of higher productivity. It is a happy ending motivated by everybody’s desire to make more money. You can imagine the biopic–a close zoom on Bradley Cooper in a wig, seated in a midcentury-modern office, dramatic pause, and then "No, not a break for coffee...a coffee break."

The story of the coffee break is also typical in that what I just said is a fairytale–it’s a myth in which one talented worker “invents” a big idea, and then after a little drama everybody comes to a mutually beneficial arrangement that we now understand to be the good and rightful status quo. However much George Cecil or the Pan-American Coffee Bureau moved the needle, taking a break at work (even specifically to drink coffee) did not begin in the 1950s or the 1920s and it did not begin with one copywriter or one ad agency.

Nor, for that matter, one town. Some locales, like Buffalo, claim even earlier credit, although this seems to me like saying you invented cracking open a cold one with the boys. You know, sure, if it's that important to you.

What we do know, and what is actually important, is that the breaks themselves were fought for and won in workplaces and courts and union contracts, and management was the enemy who interfered at every step. While ad men and small-town docents argue over who came first, we have dozens of stories of rank-and-file workers fighting for a dignified respite on the job.

And the reward for all this organizing and fighting? To this day, the coffee break is a metaphor for office slackers. Managers today still cheat workers out of their legally mandated breaks, coffee or otherwise. The progress still to be made reminds us that early victories were incomplete. They were, we should still remember, victories nonetheless, rare but essential Ws on the scoreboard of American labor.

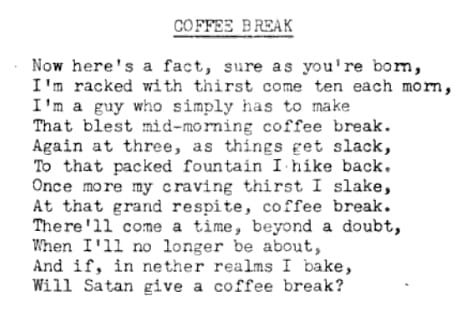

I’ll leave you with a poem that, to be honest, I can’t fully source. This ditty made the rounds circa 1951, credited to a Herbert E. Smith. It was syndicated in the humor sections of at least seven newspapers and five magazines across the country (including the delightfully named Sheep and Goat Raiser: The Ranchman's Magazine). Maybe a better historian could track this poet down, or maybe like a lot of working class art the details are lost to time.

Background reading

Koehler, Franz A. Coffee for the Armed Forces. 1958.

Meister, Ever. "Coffee History: The Coffee Break." Serious Eats.

Watkins, Julian Lewis. The 100 Greatest Advertisements. 1959.